Last Friday, the SEC’s Market Structure Subcommittee released its draft recommendation on decimalization and tick sizes. In a refreshingly clear analysis, it recommended that the SEC not experiment with artificially increasing the tick sizes for small-cap companies.

“Engaging in pilot programs, when we know what occurs from prior experience (and it is not good for investors) seems unjustifiable.

The basic question at issue is whether increasing tick sizes of small-cap stocks to a nickel (or more) will help the US economy by making it easier for small companies to access capital through the public markets.

The advisory committee did a clear, concise job of exploding the arguments in favor of a pilot. In summary:

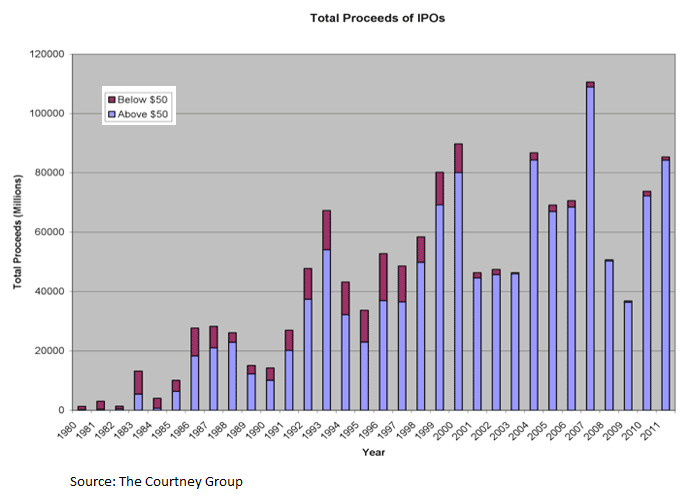

- Decimalization did not cause the decline in small company IPOs over the past couple of decades – the growth of the private markets is a much more likely primary cause (though there may be several factors).

- Wider tick sizes will increase transaction costs for investors and increase revenues for market makers. “Any increase in minimum tick size would disproportionately harm retail investors, who would see their trading costs artificially inflated above the rate set in competitive markets.”

- More profits for market makers won’t help small companies. Market makers and wholesalers “do not currently have research or investment banking operations. If tick sizes increase, it seems highly likely that any additional profits will simply be retained by these trading centers or shared with firms that send them order flow, rather than being directed into increased research or other activities to benefit capital formation.”

- Larger quoted size at a worse price doesn’t equate to increased liquidity for institutional investors. Market makers don’t hold positions; they are only short-term intermediaries between long-term investors. Increasing the profits of intermediaries must increase transaction costs for institutional investors.

Finally, a comment from the committee on the cavalier attitude taken on by some proponents of a pilot:

Indeed the lack of focus on the impact on investors from the proponents of higher spreads is noticeable and gravely concerning. Compounding these concerns are the incentives faced by various market participants who stand to profit from larger tick sizes; the harm of moving away from decimalization is borne primarily by retail investors diffusely, while the benefits to market makers are very highly concentrated, making their voices more dominant in this debate.

Can a Pilot Even Help?

Despite the clarity and persuasiveness of the recommendation, the SEC reportedly may forge ahead with a pilot. The decision may come down to the political imperative to act. The push for action is well captured in a “dissenting opinion” authored by one of the committee members. Disappointingly, the dissenting opinion ignores the specific, well-reasoned, and footnoted analysis provided in the subcommittee’s report, and simply relays the opinions of “experts” and “investors” that decimalization is to blame for lack of liquidity and volatility of small companies.

Putting aside the merits of the different sides of the debate, the biggest challenge for the commission is how to evaluate the success of a pilot. The dissenting opinion suggested multiple experimental groups and a control group, which on the surface looks like good experimental design. The idea is that we can look for differences between experimental and control groups. So, for example, if during the pilot there is a global boom that increases trading activity and IPOs across the board, these effects will be seen in all the groups and won’t be attributed to the experimental condition of the pilot. It should let us tease out the effects that are due to the differences between the experimental conditions.

But there is a fundamental problem here. The key question under debate is whether deeper quotes at larger tick increments will lead to more small-cap listings. The committee believes it won’t, and the dissent believes it will. But any pilot that doesn’t directly measure the number of new small-cap listings can’t resolve this debate. We are certain to see significant differences in market metrics like quote size among experimental and control groups. But if the bearing of these metrics on the ultimate objective of encouraging small companies to go public is not agreed on, the structure of the pilot as an experiment is fundamentally and fatally flawed, and incapable of achieving its objectives.

So what about looking directly at the number of IPOs? This also seems hopeless. It doesn’t allow for a control group, because new listings can’t be associated with a particular experimental group among the set of existing stocks; the decision to go public has to do with what each individual firm thinks will happen after its own offering. And without a control group, even if a pilot were to last five years, it would be impossible to convincingly attribute any change in the level of IPOs during that period to this market structure change, as opposed to the other elements of the JOBS act (some of which are designed to allow small companies to avoid having to go public), or the overall economy for that matter.

Meanwhile, the key tools in the SEC’s toolbox for understanding the negative impact on investors – trading costs – are all but certain to show immediate harm to investors from increasing the tick size.

First, Do No Harm

We hope that the SEC listens to its advisory committee. Although proponents of the pilot – many genuinely well-meaning – will impugn this decision as “do-nothing,” given the experiences of the past decade with the unintended consequences that can be caused by well-intended regulation, the SEC would be wise to follow the model of physicians and “first do no harm.”

If the Commission nevertheless decides to proceed with a pilot, we urge it to clearly describe and seek public comment on structure of the pilot, with particular clarity on what criteria will be used to determine whether a given experimental market structure will lead to an increase in small-cap IPOs.